- AUST POST SHIPPING

- 0438 654 235

- info@recoverycurios.com

- P.O. Box 7640 Cairns QLD Australia, 4870

-

0

Shopping Cart

MESSERSCHMITT BF-110 LN+ER 40CM LONG, FUSELAGE RELIC

In the aftermath of WWI, the US public were determined to never again commit troops or resources to foreign wars and in the early 1930s passed a series of laws which became known as the Neutrality Act. The Act prohibited the export or transportation of arms, ammunition, and implements of war to belligerent countries by vessels of the United States.

In the aftermath of WWI, the US public were determined to never again commit troops or resources to foreign wars and in the early 1930s passed a series of laws which became known as the Neutrality Act. The Act prohibited the export or transportation of arms, ammunition, and implements of war to belligerent countries by vessels of the United States.

It was a confusing time for the US as Germany continued to extend its influence across mainland Europe.

Canada however had no such restraints and its ships were already crossing the North Atlantic with troops and supplies to aid their British allies whilst the Commonwealth Air Training Scheme was providing fighter and bomber crews from a number of Flight Schools across the Commonwealth.

With the German invasion of Poland in 1939, US neutrality was no longer an option and the US Lend Lease program, which allowed for the supply of military

With the German invasion of Poland in 1939, US neutrality was no longer an option and the US Lend Lease program, which allowed for the supply of military  equipment on credit to assist allies defend themselves was soon implemented. The US did not officially declare war with Germany until after the Japanese attack on its naval base at Pearl Harbour in December 1941 but until then, US destroyers were already accompanying the many troop and supply ships crossing the North Atlantic under the dubious argument that they were simply protecting their investments.

equipment on credit to assist allies defend themselves was soon implemented. The US did not officially declare war with Germany until after the Japanese attack on its naval base at Pearl Harbour in December 1941 but until then, US destroyers were already accompanying the many troop and supply ships crossing the North Atlantic under the dubious argument that they were simply protecting their investments.

For the Germans looking at consolidating their gains in Poland whilst preparing for further military action into Northern Europe, the possibility of the Allies establishing a resupply route into Russia across the Arctic and Barent Seas from British bases at Scarpa Flow was a  significant threat and became a key factor in launching its 9 April 1940 invasion of Denmark and Norway. With the aim of securing ice-free harbours from which its naval and airforces could gain control of the all northern approaches, Operation Weserübung was begun.

significant threat and became a key factor in launching its 9 April 1940 invasion of Denmark and Norway. With the aim of securing ice-free harbours from which its naval and airforces could gain control of the all northern approaches, Operation Weserübung was begun.

Norway was largely unprepared for the German military invasion when it came on the night of 8–9 April 1940. The surprise attack, and the lack of preparedness of Norway for a large-scale invasion of this kind resulted in the country being completely overrun although Norwegian naval and airforces were able to hold off the attackers long enough to allow the Royal Family to escape to England.

Norway was largely unprepared for the German military invasion when it came on the night of 8–9 April 1940. The surprise attack, and the lack of preparedness of Norway for a large-scale invasion of this kind resulted in the country being completely overrun although Norwegian naval and airforces were able to hold off the attackers long enough to allow the Royal Family to escape to England.

British troops sent to help defend the strategic Norwegian port of Narvik encountered strong opposition from the already entrenched German forces whilst the RAF who had been flying reconnaissance patrols were attacked by German fighters which had been hastily sent north.

British troops sent to help defend the strategic Norwegian port of Narvik encountered strong opposition from the already entrenched German forces whilst the RAF who had been flying reconnaissance patrols were attacked by German fighters which had been hastily sent north.

With the German  invasion of France a few months later, Britain quickly realised they could not sustain their attacks in the North whilst their troops were being routed in the South and evacuated their forces from the Northern

invasion of France a few months later, Britain quickly realised they could not sustain their attacks in the North whilst their troops were being routed in the South and evacuated their forces from the Northern  Fjords surrendering the region to German forces.

Fjords surrendering the region to German forces.

For the next 8 months, the German’s consolidated their control over the region and apart from some minor skirmishes with local partisans and the occasional British reconnaissance overflights and attacks on some southern bases, the Luftwaffe maintained few aircraft in the area but moves were afoot to change this.

On the 31 December 1940, eight lieutenants, who had recently graduated from blind flying school (ELF 2) near Leipzig, gathered in Berlin to receive their new postings to Norway. The lieutenants were F. Brandis, W. Dietrich's, M. Francisket, D. Klappenbach, F. Laskowitz, K.-F. Schlossstein, H. Wiedebentt and D. Weyergang. A few days later they travelled through Sweden by train along with their radio gunners and support personal.

On the 31 December 1940, eight lieutenants, who had recently graduated from blind flying school (ELF 2) near Leipzig, gathered in Berlin to receive their new postings to Norway. The lieutenants were F. Brandis, W. Dietrich's, M. Francisket, D. Klappenbach, F. Laskowitz, K.-F. Schlossstein, H. Wiedebentt and D. Weyergang. A few days later they travelled through Sweden by train along with their radio gunners and support personal.

Arriving in the Norwegian capital of Oslo, they transferred to a well provisioned Junkers JU 52 Transport for the 454 km flight to the lone outpost of Kevik with its single potholed runway and dilapidated outbuilding  scattered along its perimeter. There they formed the Kommando Kjevik, an airforce unit which had yet to receive any operational aircraft or a commanding officer.

scattered along its perimeter. There they formed the Kommando Kjevik, an airforce unit which had yet to receive any operational aircraft or a commanding officer.

In the days that followed, a number of war weary Bf 110Cs finally arrived from the heavy fighter group III./ZG 76 which had spearheaded the invasion of Poland and the early attacks on Denmark and Norway. Brandis (pictured right & above right), the oldest of the Lieutenants was appointed Unit Commander. Four days later, they flew their first mission.

In the days that followed, a number of war weary Bf 110Cs finally arrived from the heavy fighter group III./ZG 76 which had spearheaded the invasion of Poland and the early attacks on Denmark and Norway. Brandis (pictured right & above right), the oldest of the Lieutenants was appointed Unit Commander. Four days later, they flew their first mission.

Although the British had placed their military aspirations of ousting the Germans from Denmark and Norway on the back burner, they still continued to mount patrols along the coast of Norway.

On the morning of 8th February 1941, Lockheed Hudson I, P5128, UA-H, of 269 Squadron Royal Air Force took off from RAF Wick at Scarpa Flow for another patrol along the Norway coast. With its crew of four, Pilot Officer Eric Alan Tingey, Sergeants Robert Wilson Baker, Edward Cottingham and Hugh Denis McNabb, they took up station slightly southwest of the city of Stavanger which had become an important railway link between the large German airbase at Sola and the rest of the country.

On the morning of 8th February 1941, Lockheed Hudson I, P5128, UA-H, of 269 Squadron Royal Air Force took off from RAF Wick at Scarpa Flow for another patrol along the Norway coast. With its crew of four, Pilot Officer Eric Alan Tingey, Sergeants Robert Wilson Baker, Edward Cottingham and Hugh Denis McNabb, they took up station slightly southwest of the city of Stavanger which had become an important railway link between the large German airbase at Sola and the rest of the country.

That same morning, two Bf110’s led by Kievik’s Commander Brandis' LN+A (pictured opposite) alongside Lieutenant Dietrich Weiergang's LN+E in the second Bf110, were informed of the incursion by German radar and took off from their base to intercept the intruders.

That same morning, two Bf110’s led by Kievik’s Commander Brandis' LN+A (pictured opposite) alongside Lieutenant Dietrich Weiergang's LN+E in the second Bf110, were informed of the incursion by German radar and took off from their base to intercept the intruders.

Mission reports are sketchy but it appears that Lieutenant Dietrich Weiergang's Bf110 engaged with the Hudson a short while later resulting in the RAF Hudson crashing into the sea. There were no survivors.

It was to be the first air victory for the Kievik Command and a few months later after returning from leave with three dachshund puppies, Lieutenant Dietrichs named one of them "Lockheed" after their first victory.

It was to be the first air victory for the Kievik Command and a few months later after returning from leave with three dachshund puppies, Lieutenant Dietrichs named one of them "Lockheed" after their first victory.

With secret plans for the invasion of Russia already in play, Brandis was informed that JG77 was going north to provide air support for the new war with Russia. Many in the squadron believed it would be a relatively short campaign and as Brandis’ air gunner writing home was to remark ‘we literally just grabbed our toothbrushes and spare underpants and took nothing else with us’.

By June 23, just one day after the start of the Russian invasion, Brandis and his group of eight Bf’110’s, arrived at their new base at Hoybukten airfield in Kirkenes.

By June 23, just one day after the start of the Russian invasion, Brandis and his group of eight Bf’110’s, arrived at their new base at Hoybukten airfield in Kirkenes.

Just days into opening of the new front against the Russians, the German High Command were expecting a quick British reprisal with a possible attack on their Norwegian naval bases. As a consequence JG77 found themselves sharing their airfield with 36 JU 87s, 9 JU 88s and a contingent of a dozen or so Bf109’s. It was to mark the start of a bitter and costly air war for Brandis and his JG77 Group.

Only 120km to the North West lay the Russian naval port of Murmansk which has become key link between Russia and the Western Powers with tonnes of munitions, aircraft and tank parts, food and raw materials offloaded daily from the Allies Arctic Convoys.

Only 120km to the North West lay the Russian naval port of Murmansk which has become key link between Russia and the Western Powers with tonnes of munitions, aircraft and tank parts, food and raw materials offloaded daily from the Allies Arctic Convoys.

The Luftwaffe had already been mounting bombing attacks on the port from their bases in Finland but now having a fully operational Bomber/Fighter Group only 120kms to the South, Kirkenes soon became the staging point for the Germans campaign to close down this essential Russian supply port.

The first raid was conducted on June 29 when, escorted by Brandis Bf110’s, a flight of JU 88 dive bombers attacked the Russian aerodrome in Gryaznaya Bay and shipping in Murmansk's Polyarny harbour. Despite heavy anti-aircraft fire from shore and ship batteries, the bombers managed to destroy the central power station as well as mount an attack on the Krasny Gorn shipyard but the later attacks were successfully beaten off by the coastal defences.

The first raid was conducted on June 29 when, escorted by Brandis Bf110’s, a flight of JU 88 dive bombers attacked the Russian aerodrome in Gryaznaya Bay and shipping in Murmansk's Polyarny harbour. Despite heavy anti-aircraft fire from shore and ship batteries, the bombers managed to destroy the central power station as well as mount an attack on the Krasny Gorn shipyard but the later attacks were successfully beaten off by the coastal defences.

Two days later Brandis’ twin-engined fighters were escorting the Ju 88s on a raid on the Niva Airfield when they were confronted by a squadron  of Soviet Polikarpov I-153 and Polikarpov I-16 biplane and monoplane fighters. Whilst the Soviet aircraft were no match for the Bf110’s, together with the increasing

of Soviet Polikarpov I-153 and Polikarpov I-16 biplane and monoplane fighters. Whilst the Soviet aircraft were no match for the Bf110’s, together with the increasing  ferocity of the Russian air defences in and around Murmansk, Brandis soon realised that future raids were going to be increasingly challenging. He was not wrong.

ferocity of the Russian air defences in and around Murmansk, Brandis soon realised that future raids were going to be increasingly challenging. He was not wrong.

A day later on another raid on the Murmansk bases, five German aircraft were downed by enemy ground fire and Soviet Polikarpov I-16s with the Bomber Group’s commander, Hauptmann E. Röger being amongst those lost.

A day later on another raid on the Murmansk bases, five German aircraft were downed by enemy ground fire and Soviet Polikarpov I-16s with the Bomber Group’s commander, Hauptmann E. Röger being amongst those lost.

JG77 had avoided any losses or severe damage in all the raids since their detachment north but this was to tragically change on July 5 when Brandis’ BF110s escorted the JU 88s and 87’s on the heavily defended port of Polyarnoye. At the time, the harbour was full of recently arrived Arctic convoy ships and Allied submarines and the

JG77 had avoided any losses or severe damage in all the raids since their detachment north but this was to tragically change on July 5 when Brandis’ BF110s escorted the JU 88s and 87’s on the heavily defended port of Polyarnoye. At the time, the harbour was full of recently arrived Arctic convoy ships and Allied submarines and the  Soviets had substantially increased the fire power of their shore-based anti-aircraft batteries.

Soviets had substantially increased the fire power of their shore-based anti-aircraft batteries.

Coming in low on their strafing runs, the Soviet shore batteries opened up directing a withering barrage of fire against the oncoming Bf110s. Brandis Group immediately scattered but as Bf 110 LN+ER (Werk.Nr. 3235) piloted by Dietrich Weyergang and his wireless-operator/gunner Kurt Tiggis pulled up to escape the onslaught, their aircraft took a  direct hit from one of the shore batteries, crash-landing at the Northern tip of Litsa Bay in a massive explosion.

direct hit from one of the shore batteries, crash-landing at the Northern tip of Litsa Bay in a massive explosion.

Both Dietrich and Kurt died in the crash and their bodies were recovered by a Finnish ski patrol some nine days later.

Both Dietrich and Kurt died in the crash and their bodies were recovered by a Finnish ski patrol some nine days later.

The wreckage was to lay tangled and overgrown at the top of the bay for almost 60 years before a local aviation historical group uncovered the wreckage; documenting its history and relocating some of the larger sections of the Bf110 to a regional museum.

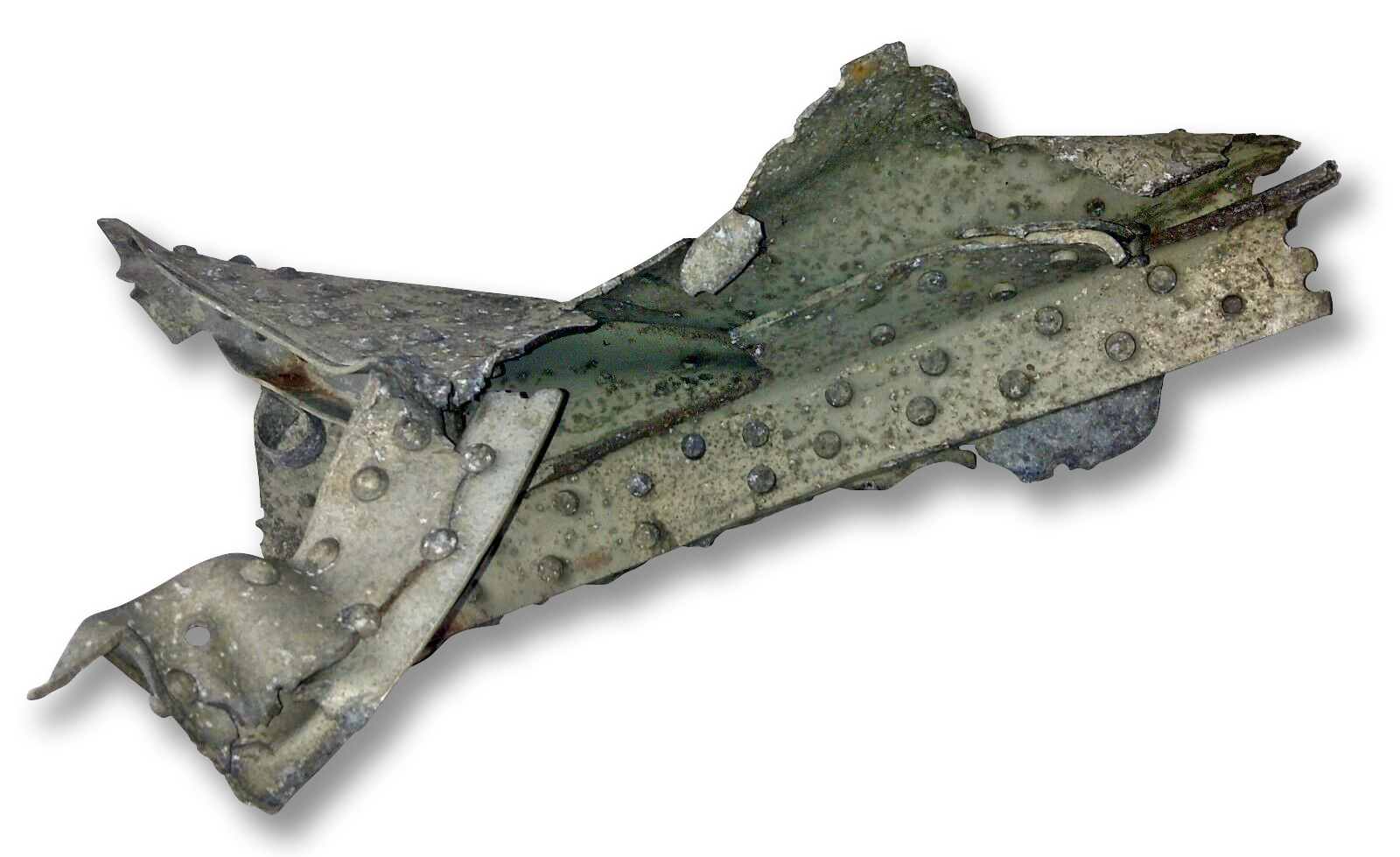

Over the years various smaller sections of the wreckage were recovered, one of which is seen here.

Part of the Bf’110s airframe between the wing root and the fuselage this 40cm long, Bf 110 original crash wreckage displays the heavy frame reinforcement, and riveting securing the aircraft’s thick aluminium skin to its frame. The outer skin still features some of Bf 110 LN+ER’s original camouflage paintwork.

Mounted on its 100yr old Mango wood display stand with engraved plaque and super detailed, hand crafted and airbrushed 1/48scale model of Lieutenant Dietrich Weiergang's Bf110 perched above on its magnetic display arm with accompanying detailed printed and laminated Fact Sheet, this Recovery Curios Original Aircraft Instrument Display would make an amazing gift for any aviation enthusiast looking to obtain their own authentic piece of WWII aviation history.

Mounted on its 100yr old Mango wood display stand with engraved plaque and super detailed, hand crafted and airbrushed 1/48scale model of Lieutenant Dietrich Weiergang's Bf110 perched above on its magnetic display arm with accompanying detailed printed and laminated Fact Sheet, this Recovery Curios Original Aircraft Instrument Display would make an amazing gift for any aviation enthusiast looking to obtain their own authentic piece of WWII aviation history.

*** NOTE..I have an absolutely stunning 1/48 scale super detailed BF110 to go with this relic complete with highly detailed metal photo etched parts. Unfortunately given that some customers will opt for wheels & flaps down with canopy opened, whilst others request wheels up in flight mode, I don't start building the model until the item is purchased so I know what is required but check out the other mounted instruments such as the Lancaster products and you'll get a good idea of just how fantastic the whole Collectable will look together on its beautiful mango wood stand.

This Messerschmitt BF 110 Collectable comes complete with detailed Scale Model, Mango Wood Stand & Plaque plus Printed Fact Sheet featuring photo of instrument in aircraft cockpit.

Return to Messerschmitt Bf 110 MAIN PAGE

Return to Vintage Aviation Collectables MAIN PAGE

Your original, airframe crash relic from Dietrich Weyergang's Bf 110 LN+ER, Original Recovery Curios Warbird Collectable includes:

- Original Warbird instrument

- Highly detailed hand-built and airbrushed 1/72 plastic scale model of the aircraft*

- Hand-crafted and beautifully finished 100yr, Far North Queensland Mango Wood display stand

- Detailed, 2-sided, printed and laminated Instrument Fact Sheet detailing aircraft and instrument

- Removable Magnetic Display Arm

*The 1/72 scale hand-built and airbrushed plastic model is available with 'wheels & flaps up or down' and 'canopy open or closed' in Dietrich Weyergang's Bf 110 original markings and camouflage or choose the amazingly extra detailed larger 1/48 scale at just an extra $45 (click on Product Option at top of page)

Upon order placement you will receive an email asking for your preferred configuration.

Your complete Recovery Curios Original Instrument Collectable is securely packed and delivery normally takes between 4 - 6 weeks approx.

Did you fly, crew or maintain a Bf110 or have a friend, colleague or family member who did? Check out our PERSONALISED ORIGINAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTABLE OPTION here.

- LAND

- SEA

- AIR

- VINTAGE ORIGINAL AIRCRAFT INSTRUMENTS

- HAWKER TYPHOON

- VICKERS WELLINGTON

- FAIREY GANNET

- RYAN ST-A SPORTS TRAINER

- DE HAVILLAND TIGER MOTH

- HAWKER HUNTER

- Mc DONNELL DOUGLAS KC-10 AERIAL TANKER

- SOPWITH CAMEL

- AIRCO DH.1 AND DH.2

- JUNKERS JU 87

- CURTISS C-46 COMMANDO

- HANDLEY PAGE HAMPDEN

- SUPERMARINE SEAFIRE

- B-25 MITCHELL BOMBER

- BRISTOL BLENHEIM

- ENGLISH ELECTRIC LIGHTNING

- HAWKER TEMPEST MkVI

- YAKOVELOV YAK - 3

- FOCKE-WULF FW190

- FOLLAND GNAT

- AIRSPEED OXFORD

- SHORT STIRLING

- AVRO ANSON

- DOUGLAS C-133 CARGOMASTER

- HANDLEY PAGE VICTOR BOMBER

- DE HAVILLAND SEA VENOM

- VICKERS VALIANT BOMBER

- DOUGLAS A-26 INVADER

- GRUMMAN S2F TRACKER

- SUPERMARINE SPITFIRE

- LOCKHEED P2-V NEPTUNE

- P-51 MUSTANG

- BRISTOL BEAUFIGHTER

- DE HAVILLAND MOSQUITO

- B-26 MARTIN MARAUDER

- P3 ORION

- DOUGLAS A-20 HAVOC

- P-39 AIRACOBRA

- AVRO SHACKLETON

- B-17 FLYING FORTRESS

- B-24 LIBERATOR

- MESSERSCHMITT BF-110

- MESSERSCHMITT BF-109

- BRISTOL BEAUFORT

- KAWASAKI Ki-45 (NICK) INTERCEPTOR

- C-130 HERCULES

- CAC BOOMERANG

- AVRO LANCASTER

- GRUMMAN F4F WILDCAT

- F4U VOUGHT CORSAIR

- WESTLAND LYSANDER

- P-47 REPUBLIC THUNDERBOLT

- NORTH AMERICAN T-6 TEXAN - HAVARD

- C-47 SKYTRAIN

- DOUGLAS SBD DAUNTLESS

- CAC WIRRAWAY

- PBY CATALINA

- P-40 WARHAWK

- FAIREY SWORDFISH

- P-38 LIGHTNING

- HAWKER HURRICANE

- CURTISS SB2C HELLDIVER

- GRUMMAN F6F HELLCAT

- SEAKING HELICOPTER

- SEAHAWK HELICOPTER

- DOUGLAS A4G SKYHAWK

- GRUMMAN TBF AVENGER

- HANDLEY PAGE HALIFAX

- DOUGLAS SKYRAIDER AE-1

- GLOSTER METEOR

- JUNKERS JU-88

- F-86 SABRE JET

- SHORT SUNDERLAND

- B-29 SUPER FORTRESS

- F-9F GRUMMAN PANTHER

- F-100D SUPER SABRE

- BELL UH-1 HUEY HELICOPTER

- AVRO VULCAN STRATEGIC BOMBER

- CANBERRA BOMBER

- DHC-4 CARIBOU

- BLACKBURN BUCCANEER

- DE HAVILLAND VAMPIRE JET

- HAWKER SEA FURY

- LOCKHEED HUDSON

- LOCKHEED EC-121 WARNING STAR

- SEPECAT JAGUAR

- HAWKER SIDDELEY NIMROD

- HAWKER SIDDELEY HARRIER

- ARADO AR 196

- VOUGHT OS2U KINGFISHER

- LOCKHEED ELECTRA

- NORTHROP P-61 BLACK WIDOW

- BOEING CH-47 CHINOOK

- LOCKHEED PV-1 VENTURA

- BOEING P26-A 'PEASHOOTER'

- Ilyushin Il-2 ‘Sturmovik’

- WESTLAND WESSEX

- FAIREY FIREFLY

- VINTAGE AVIATION COLLECTABLES

- VINTAGE COLLECTABLE MODEL AIRCRAFT KITS

- RETRO STYLE METAL AIRCRAFT COLLECTABLES

- VINTAGE ORIGINAL AIRCRAFT INSTRUMENTS